In the 1930s, gastric cancer (which then was mainly cancer of the lower stomach) was the most common cause of cancer deaths for American men. However, over the course of the 20th century, classical cancer of the lower stomach became much less common; probably because of the use of refrigeration as the principal means of food preservation rather than salt-based food preservation. Conversely, over the last 30 years cancers of the upper stomach and junction of the esophagus and stomach have increased greatly — mainly related to an increase in obesity, gastroesophageal reflux disease and related changes of the lining of the lower esophagus (Barrett’s esophagus).

Overall, the epidemiology of stomach cancer has multiple facets with great variations based on geographic location, race, age, and lifestyle.

There is a bacterial organism called helicobacter pylori which can cause chronic inflammation of the lining of the stomach and over time precancerous lesions.

The risk of stomach cancers is doubled for smokers.

Certain genetic factors can result in an increased stomach cancer risk.

There are families who have a mutation in a gene called CDH1 (also called E cadherin) which encodes a cell adhesion protein. Over two thirds of affected patients will develop gastric cancer and often a prophylactic gastrectomy is warranted. Affected women are also at risk for lobular breast cancer.

Another genetic syndrome called Lynch syndrome in which affected patients carry genetic mutations in DNA mismatch repair genes is not only associated with a high risk of cancers of the colon and rectum, but also with an increased risk of gastric cancer and other cancers.

Mutations in the breast cancer genes BRCA1 and BRCA2 also confer an increased risk for the development of gastric cancer.

Research To Improve Survival Outcomes

When patients are diagnosed with stomach cancer, up to two thirds of patients will have advanced disease. In order to improve treatment outcomes beyond the benefits of chemotherapy, a lot of research has focused on targeting signaling pathways of the gastric cancer cell.

The Her2/Neu/c-erb-2 protein belongs to a group of cell receptor proteins called human epidermal growth factor receptors. It is overexpressed in 15 to 37% of patients with advanced gastric cancer and targeting it with a Her2 specific monoclonal antibody in addition to chemotherapy has shown to improve treatment outcomes.

Another cell receptor called Her1/EGFR/c-erbB1 is overexpressed in 30 to 80% of patients with gastric cancer. However monoclonal antibodies targeting Her1/EGFR have not proven to be beneficial.

The formation of new blood vessels (angiogenesis) has been identified as an important factor in the development and progression of stomach cancer. Particularly a blood vessel formation receptor called VEGFR-2 appears to play a central role in the promotion of blood vessel formation and tumor growth.

Two recent studies showed that a new monoclonal antibody targeting VEGFR-2 either by itself or when added to chemotherapy improved gastric cancer treatment outcomes and has been approved by the FDA for the treatment of patients with advanced gastric cancer where the cancer has worsened after initial chemotherapy.

Another pathway under intensive investigation is the MET/hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) signaling pathway. The MET proto-oncogene encodes the receptor tyrosine kinase c-MET. MET activation leads leads to tumor cell detachment, migration and invasion and has been associated with a poor prognosis.

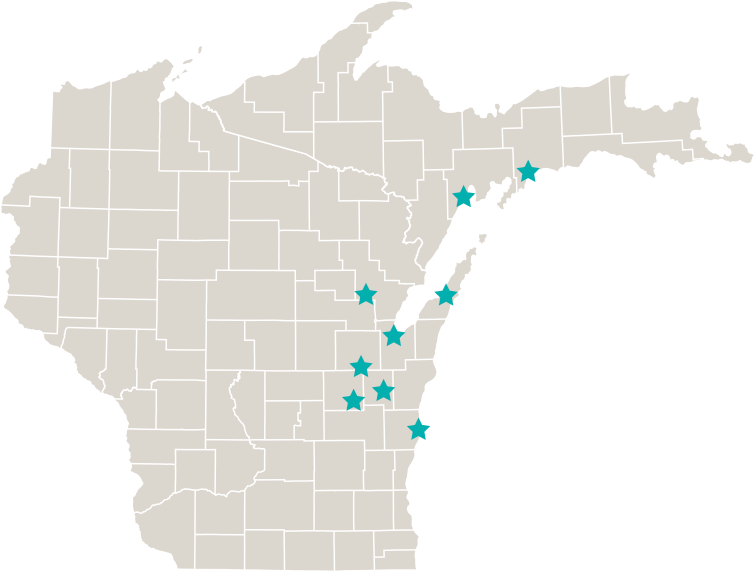

There are presently two ongoing larger nationwide studies looking at the use on monoclonal antibodies targeting the MET/HGF pathway, but it will be some time before results of those studies will be available.

In conclusion, it is exciting to see such a flurry of research activity looking at novel treatment strategies for our patients with stomach cancer, and I am hopeful that survival outcomes will continue to improve.