Picture a common movie scenario: the police have the bad guys surrounded, locked down inside a building – but there are hostages in there too, and if the cops go in shooting they won’t be able to tell the victims from the villains.

“Die Hard”, “Inside Man”, and “The Dark Knight Rises” have all done variations on this idea. I bet you can even think of a few more.

But this familiar movie scenario can help us better understand the difficulty the immune system has trying to fight cancer, and how the new class of cancer drugs called checkpoint inhibitors can overcome it.

So, let’s apply our “bad-guys-with-hostages standoff” analogy to an immune system trying to eradicate cancer, and see what we can learn:

- Your immune system, like a good police officer, must sometimes restrain itself. A SWAT team storming in at every opportunity can cause terrible collateral damage, just as an unrestrained immune system can cause terrible diseases like rheumatoid arthritis and lupus. That’s why your immune system’s T-cells have special receivers sticking out of them like antennae dishes, listening for the signal to “stop” – and when the T-cell gets that signal, it backs off. We call these “stop signal” receivers checkpoint inhibitors – one of which is PD1.

- Some cancer cells fool the immune system the same way the villain fooled Bruce Willis in “Die Hard”. When Bruce Willis’ character got the drop on the main villain Hans Gruber (who he’d spoken to but never seen), Hans faked an American accent and passed as a hostage (“Oh no please don’t shoot, you’re one of them aren’t you…”). In a similar way, some cancer cells have learned how transmit the “stop” signal by making a special molecule that sticks from its surface and binds to PD1 on attacking T-cells – which turns them off. We call this “stop signal” molecule PDL1.

- Preventing the PDL1 “STOP” signal from reaching T-cells invigorates the immune system enough to attack some cancers. Drugs like nivolumab and pembrolizumab (which interrupt the PD1/PDL1 interaction) put the fight back into the T-cells, allowing them to attack the cancer – but with much less of the “collateral damage” that we’ve seen in other types of immune enhancers.

Here’s a video that explains the process visually.

We should celebrate the success of these drugs, but have to remember that no cancer drug in history has ever been a “cure-all”. We have to remember that there a great many more checkpoint inhibitors than PD1, so there’s many other ways for cancer cells to escape the immune system.

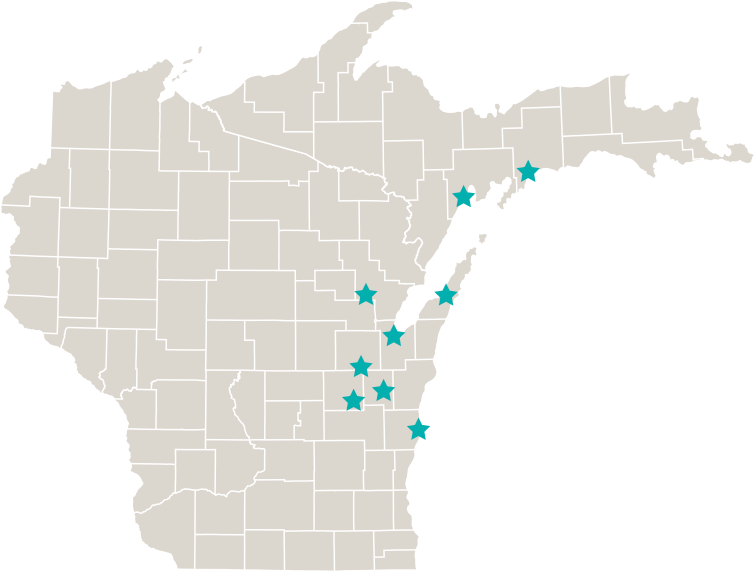

We have to remember we still need good clinical trials, and patients willing to participate in them.